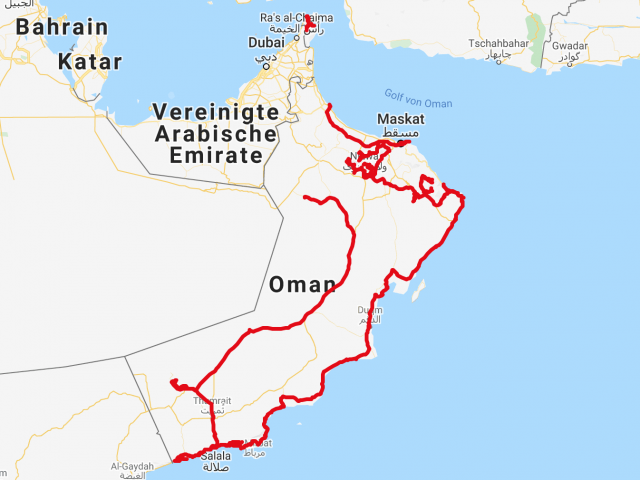

The Pamir Highway is one of the few dream roads that every overlander would like to drive at least once in their lifetime. The name “highway” is initially misleading, as it consists mostly of small tracks carved into the rocky mountain landscape, winding along a deep river valley on the immediate border with Afghanistan. Furthermore, there isn’t just one highway, but several variants (the northern and southern routes from Dushanbe to Qalai Khumb, with or without the Wakhan Valley, etc.). However, the Pamir Highway is also an important part of the “New Silk Road” project and is currently being intensively developed by the Chinese. Furthermore, you often see Chinese trucks and car transporters. Some new Chinese cars are also transported individually, which gives the phrase “transportation kilometers” a whole new meaning 😉.

We set off from Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, with great anticipation and opted for the better-developed southern route. We ride so leisurely along the best asphalt road down to the Panj River – the border river with Afghanistan – that at first we can hardly believe we’re on the legendary Pamir Highway. This has the clear advantage that the driver can also fully enjoy the magnificent scenery and doesn’t have to constantly concentrate on the road. From Qualai Khumb onwards, the situation changes abruptly: the road, which from here on is truly bad, is undergoing intensive construction work, including blasting, tunnels, etc. We set off at 5:00 a.m. specifically to get through the construction works before the road closures. Accordingly, we were surprised when we soon reached the end of a line of trucks. Our tried-and-tested strategy of just driving past the waiting trucks unfortunately didn’t help this time: a truck’s trailer crashed into the Panj Riverbed, making passage at this narrow spot for other vehicles impossible. So we, too, had to wait for six hours until the road was temporarily widened somewhat by hand (shoveling by the waiting truck drivers). At least we were in pole position and were therefore one of the first trucks to pass before other trucks got stuck or slided into the river (which is not entirely unlikely given the condition of the trucks and the skill of some of the drivers). Furthermore, we didn’t encounter any construction sites along the rest of the route since it was a holiday, although we only found out about this later.

Unfortunately, you’re not allowed to spend the night in the main valley along the Panj River because of the immediate border with Afghanistan. The military patrols intensively and will send you away because “the Taliban might shoot you.” What nonsense! They simply have a drug problem, and when the two sides are fighting over opium at night, you obviously don’t want to be caught in the middle of it. After a short detour into the spectacular Bartang Valley, we continued on to the small town of Khorog. With 30,000 inhabitants, it is the center of the autonomous province of Gorno-Badakhshan, which covers almost half the area of Tajikistan but has only a fraction of the population. It is very distinctive in terms of culture, language (Pamir), etc. We fill up again, as this is the last chance to get decent-quality diesel. The food supply, however, is very limited. Unfortunately, the weekly Afghan market, which takes place every Saturday, isn’t taking place today as yesterday was a holiday – what a pity!

We continue through dreamlike landscapes into the Wakhan Valley, where the Panj River valley widens, revealing magnificent views of the Hindu Kush with its 6,000- and 7,000-meter peaks. There are many small villages, agriculture is practiced, and the people are very friendly here, despite their poverty and extremely remote location. Various fortifications, some of them very dilapidated, testify to the strategic importance of this valley even during the times of the “old Silk Road.” The weather is very good, and so we climb higher and higher to the Kargush Pass at 4,300 meters. Altitude acclimatization now dictates our travel pace, and we sometimes only travel 30-50 km a day… which, given the quality of the trails, is perfectly adequate. Our overnight spots at the beautifully situated mountain lakes Chukurkul and Yashikul are real highlights, and we can’t stop taking photos and flying the drone.

Passing the small town of Murgab, whose very simple “container market” illustrates the harsh life and deprivation of the people in this region, we cross the 4,660-meter-high Ak Batail Pass (the highest road pass in the former Soviet Union) to Lake Karakul. Formed approximately 5 million years ago, apparently by a meteorite impact, it is by far the largest lake in Tajikistan at 380 km² and is fed by glacial waters from the surrounding mountains, which are up to 7,000 meters high. An impressive scene.

Unfortunately, the weather takes a turn: it snows overnight, and we decide to wait another day until we can enter Kyrgyzstan via the Kyzylart Pass. Although the pass, at “only” 4,280 meters, is lower than the other Pamir passes we’ve conquered so far, its descent into Kyrgyzstan should – according to various sources – only be attempted in dry conditions in rain and snow due to the very slippery clay track – especially for large vehicles like Shujaa. So we, too, had a short, externally imposed “forced break.” The next day, however, the descent was much less spectacular than everyone portrayed. Due to social media and the growing number of overlanders, some of whom try to outdo each other with their dramatic reports and thus stand out in the scene, we were also somewhat influenced. And indeed, we’ve driven on much more challenging roads.